Much of the debate around AI training programs boils down to a fundamental, if difficult to answer question: are AI apps plagiarizing the artists and writers that they study, or are they simply “learning” from prior examples, as a student would in school?

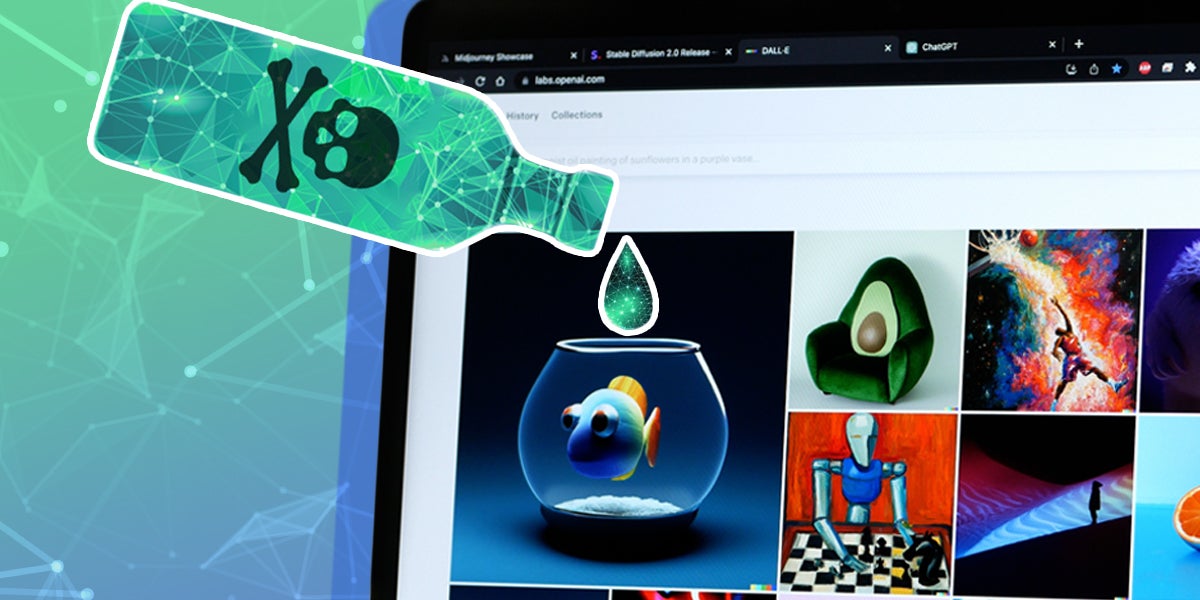

A team of researchers at the University of Chicago contends the former is more likely true. Which is why they’ve developed a new tool called “Nightshade,” which attaches itself to a visual artist’s work online, and corrupts any AI program that attempts to use the image for training purposes. According to co-creator Ben Zhao, if Nightshade spreads widely enough, it could slowly degrade generative AI models such as Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and Midjourney over time.

Deadly Nightshade

Nightshade works by making invisible changes to digital art on the pixel level. These changes then exploit a security vulnerability that’s common to AI training platforms. Rather than recognizing the core image as it normally would, Nightshade’s changes confuse the software, producing false results. (So a picture of a car reads to the program, for example, as a picture of a cow.) Because these connections between sign and signifier are so vital – allowing AI programs to get “smarter” about recognizing real-world objects and imagery by name and description over time – this kind of corruption can functionally break the program entirely.

Nightshade’s creators have also developed a tool called Glaze, which masks art styles in addition to specific objects. So for example, a realistic drawing appears to AI training software as an example of cubism or impressionism.

This is a particularly extreme, even vindictive, approach to the controversial subject of AI training and its interaction with privacy, artists’ rights, copyright, and authorship, but it’s not happening in isolation. While the early days of 2023 saw an enthusiasm toward AI and its applications that bordered on euphoric, culturally there’s been something of a months-long comedown, with an increasing number of artists and creators pushing back against having their work fully integrated into AI software.

Creatives Have Lots of Feelings

While most creatives agree that taking inspiration and even ideas from other artists is acceptable, and a not-insignificant number of people aren’t bothered by generative AI on a conceptual level, there do seem to be some big-picture concerns when it gets down to actually using these apps in real-world scenarios.

Many creatives have simply pointed out that the results, at least so far, are disappointing. In June, “Black Mirror” creator Charlie Brooker told a SXSW panel that he tried to use ChatGPT to write an episode of his popular sci-fi anthology series, only to find that the results were “boring” and “derivative.” James Cameron, whose “Terminator” films helped to popularize notions about artificial intelligence as long ago as the 1980s, fears the future weaponization of AI, but argues that it’s unlikely bots will ever write “a good story.”

For others, the fears run deeper. Filmmaker Tim Burton recently told British newspaper The Independent that he finds AI apps attempting to cop his familiar aesthetic and visual style as “disturbing,” equating it to the spiritual belief that having your photograph taken can “steal your soul.” Comedian Sarah Silverman and a collective of novelists have actually filed a lawsuit against OpenAI and Meta, claiming that their ChatGPA and LLaMA large language models illegally infringed on copywritten material while training.

Short of relying on the actual justice system to block AI from training on their work, other creatives with concerns about being ripped off by computers have started getting… well, creative in circumventing these processes. A trio of visual artists have launched a similar suit against Stability AI, as has the team behind Getty Images.

Striking the Right Balance

Make no mistake: a robust collection of diverse training materials is absolutely essential for producing a high-quality AI model. On some level, designing generative AI apps is always going to be a balance between an ethical approach that gives content creators control over how their work gets used, and creating a high-quality finished product that utilizes all relevant training materials possible. An Ars Technica piece from April, about necessarily compromises made by Google to get its Bard software keeping pace with ChatGPT, lays this tension out very clearly. AI ethics teams were “disempowered and demoralized” in the process of getting Bard developed more quickly.

Some of the companies behind generative AI apps have made attempts to reassure creators and even give them some levels of control over whether or how their work is used for training. In August, OpenAI introduced a tool that website owners can use to block automated bots from scraping their content, though at this point, it’s designed to keep out “personally identifiable information,” and not just copyrighted material that users don’t want integrated into AI systems. Representatives from Adobe, which has been upgrading its Photoshop and similar applications with new generative AI features, testified before Congress over the summer that artists should have the right to stop AI systems from training on their creative works.

Good public relations though these moves may be, the companies behind them are still heavily incentivized to suck up as much content as humanly possible. At least for now, that’s the only way to ensure that you’re designing a useful AI application that will understand basic prompts.

So short of relying on the actual justice system to block AI from training on their work, other creatives with concerns about being ripped off by computers have started getting… well, creative in circumventing these processes. Collective social media pushback was all it took to convince newspaper giant Gannett Inc. to abandon a scheme to use AI in covering high school sports, and get Zoom to reverse course on a plan to train AI based on everyone’s video conferences. Getty Images teamed with chip makers Nvidia to produce its own generative AI tool, based exclusively on publicly licensed images without copyright protection.

Still, if all else fails, thanks to The University of Chicago, there’s now at least one more option for particularly aggravated creators: sabotage.