The beauty of FlopTok, which takes our flop era and turns it into a niche online culture, has metamorphosized over the years. What began as a subsection of low-quality, ‘Stan Twitter’ memes has become an intricate online society with its own island (Floptropia), citizens (Flops), and countless other world-building techniques that would make J. R. R. Tolkien tremble.

But what exactly is FlopTok? How can you even sum it up?

“FlopTok is a TikTok-specific form of shitposting which utilizes abstract and surrealist humor,” digital culture professor Jessica Rauchberg told Passionfruit.

What sets FlopTok apart is its audience’s active role in building the community and its surrounding lore.

“FlopTokers simultaneously consume and create content that builds the genre in new and exciting ways,” Jessica explained. “Instead of simply participating as an audience member, [FlopTokers] have a unique say in contributing to FlopTok memes through remixing and restyling.”

One example of a FlopTok meme that successfully broke into the mainstream was the “Cupcakke remixes” — a series of explicit remixes of songs by rapper Cupcakke that became increasingly verbose, complex, and senseless with each reproduction.

According to digital culture journalist Kelsey Weekman, the absurdity of these memes is actually a sign of authenticity.

“We’re constantly hearing that people crave authenticity as a break from the perfectly polished social media content that’s rotting our brains, but I think what people really want is absurdity,” Weekman said. “Surreal, post-ironic, bizarre memes offer a sort of counter to that constant perfection.”

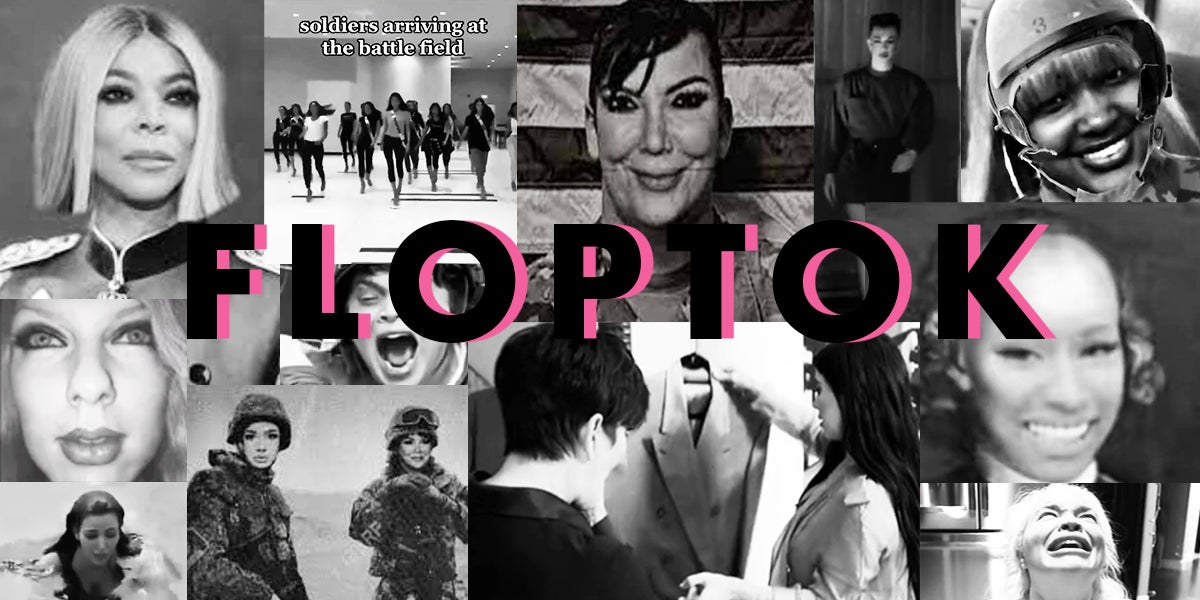

Rewind back to late 2020, in the thick of the pandemic. Back then, FlopTok was essentially a style of purposefully bad TikToks people made about being in their ‘flop era.’ But in the years since, it has developed into a deep-fried, ultra-ironic inner world including events like the “Badussy War” and figureheads such as “Founding Mothers” — two of whom look suspiciously like reality TV star Kris Jenner and rapper Cupcakke.

In case you’re wondering what the heck I’m talking about, I’ll attempt to explain this absurdist fictional landscape. Like many nations, the fictional land of Floptropica was built on bloodshed, with the near-century-long Badussy War starting in 1903. It started after Cardiac B. Arrest, supreme queen of Bussyland, tried to tear Queen Abby Lee of the Abby Lee Dance Company’s wig off. This soon escalated to Rupaul, Empress of Twinkia, Nicole Maraj, President of the United States of Barbica, and Jiafei, Queen of Products, jumping to Abby’s defense and mobilizing their respective nations. This led to The Twinks and The Dancers crossing the Barbussy border and invading Bussyland.

A large amount of FlopTok’s content, which has 19.9 billion views under the FlopTok tag, is based around this fictional war and usually consists of black and white, low-resolution edits of Kris Jenner, Nicki Minaj, and Trisha Paytas poorly photoshopped into military imagery. It’s worth remembering that the ‘poorly’ part here is especially important — the beauty of Floptok is that it all has an undercurrent of being just that little bit crappy.

And if you’re completely and utterly confused by this convoluted lore, then that’s fine, too. Firstly because there’s a full comprehensive Wiki site dedicated to the lore, and secondly, because, as media psychologist Pamela Rutledge explains, this confusion is kind of the point of FlopTok.

“FlopTok is esoteric and hard to understand by those not in the know, which enhances the value of being ‘in,’” she told Passionfruit. “The appeal of Floptropica/FlopTok to members is that it doesn’t make sense to a lot of people. ‘In-groups’ have always been defined by shared specialized content, jargon, and behaviors, from Star Trek to the Masons. This is another way of creating community, affiliation, and a sense of belonging through a fan culture.’

This “insularity” was also identified as a selling point of FlopTok by digital culture blogger Kieran Press-Reynolds.

“FlopTok seems like an insular haven for people (especially LGBTQ) to create media/myths about beloved celebrities and foster community in an often fractured and impersonal internet landscape,” Press-Reynolds told Passionfruit.

FlopTok’s subversive nature, which involves celebrating failure as opposed to disparaging it, was also identified as a selling point by Press-Reynolds, as he noted that “celebrating ‘flopping’ as opposed to victory is a fun twist.”

“There’s a kind of melodrama or soap opera aspect where failure becomes sort of endearing,” he said.

Ultimately, when it comes to FlopTok, journalist Weekman notes that while it might seem effortless on the outside, it’s actually a lot more contrived than you think.

“People who spend a lot of time online, especially people who grew up with memes and platforms and creators everywhere, respond to that weird randomness we see with FlopTok because it feels fresh, even if it’s just as performative and strategic as any other kind of humor,” she said.

“And I think it’s particularly popular on TikTok because it’s so immersive, it’s easy to find other overexposed weirdos like yourself and build a little community of content. You’re just building on memes and references instead of actually talking to each other.”