A clip from a Kai Cenat stream in which actor and wrestling legend John Cena discusses Cena’s philosophy of life, and what it means to have “purpose,” has gone viral this week. In just about a minute, Cena drops a lot of valuable insights on his young host and viewers.

The clip, and a recent viewing of Netflix’s Vince McMahon docuseries “Mr. McMahon,” got me thinking about the myriad connections between working as an online content creator and working as a professional wrestler. Obviously, in both cases, we’re talking about oversized personalities pursuing careers in media and entertainment. But on a deeper level, there are a lot of lessons and insights that creators can glean from looking back at the modern history of pro wrestling, and the kinds of successful, audience-expanding techniques and strategies that performers and promoters have been leaning on in the world of sports entertainment now for decades.

1. It’s All About Emotion

In wrestling, a “pop” refers to a positive crowd reaction (like cheering or clapping or chanting a wrestler’s name), while “heat” suggests a negative reaction or general animosity. Heroic characters (“babyfaces”) make the crowd pop when they pull off an impressive move or humiliate a bad guy, while villains (“heels”) build up heat over time by making the fans truly despite them.

What’s noteworthy here is how little difference there is between babyfaces and heels, in terms of the match or the promotion’s overall success. If you got a strong reaction from the crowd – positive OR negative – you did a great job. As a number of WWE executives and wrestling insiders explain throughout “Mr. McMahon,” emotion – love OR hate – is what sells tickets and merchandise, and keeps people watching week to week. There are dozens of examples throughout wrestling history of heels becoming fan favorites, and a number of the all-time most iconic wrestling personas – from The Rock to The Undertaker – were introduced as bad guys.

Wrestlers, of course, are just very athletic actors who are taking on personas in the ring, and everyone except the very young or gullible fundamentally recognizes this. So it’s not a 1-to-1 comparison for many online content creators, who produce videos and streams as themselves, in their own voices. They don’t have the option of making up an extreme variation of themselves and driving their audience crazy, and they’re not setting the stage for a cathartic and satisfying “comeuppance” that will conclude their story.

But there is something to be learned from this overall approach, and the idea of thinking about videos and digital media – of any format or genre – as “storytelling” on a fundamental level. When trying to grow a large, dedicated audience, your content must produce some kind of strong emotional, not purely intellectual, reaction. Informing or intriguing or enlightening viewers are all great and noble and lofty goals, but nothing guarantees a return visit like getting people personally invested in what you’re doing or saying or producing, and that means telling your viewers some kind of emotional story.

2. Remain Very Open to Feedback, and Adapt Quickly

Here’s another random clip that recently went viral on X:

It’s footage from a 2011 WWE “Hell in a Cell” match, but unlike most TV wrestling, the audio has been set up here in a way that allows viewers to hear the performers inside the ring and everything they’re saying to one another. It quickly becomes clear that Cena and CM Punk are essentially directing and choreographing the fight in real-time.

What’s even more impressive than just plotting out a chaotic brawl involving multiple people in the moment is that they’re monitoring the crowd and playing off of their reactions.

This also comes up repeatedly in “Mr. McMahon.” Wrestlers aren’t just planning out moves and then executing the stunts like a stage fight or a dance routine. They’re listening to the cheers and boos, and essentially interacting with the fans.

The parallels to online content creation here are immediate and obvious. Lots of creators come into their channels or platforms with big plans all worked out, and specific ideas about what they want to do and what they’re trying to get across. But as with Wrestlemania, social media and livestreaming are conversations that go both ways. Fans don’t just want to watch and cheer (or boo), they want to be heard and respected. Their reactions are part of the story, and if their preferences don’t eventually find some way into the narrative itself, they’ll go elsewhere and listen to someone else’s story.

This doesn’t mean a creator must cease having a voice of their own, or turn their channels over to the fans, or even stop pursuing a passion project that doesn’t immediately strike a mainstream chord. It just means keeping an open mind and clearing out the lines of communication, so that a creator’s community has an opportunity to make their voices heard.

3. Blurring the Lines Between Reality and Fiction Can Be Intriguing, but Within Limits

Just as with wrestlers, many creators do have a “larger than life” persona, which they play up in their videos. One can only hope that, when relaxing at home, the Paul Brothers or MrBeast allow themselves to bring their energy levels down a bit. Even non-professional creators who spend enough time on social media platforms start to do this over time. Your “voice” on Instagram or X isn’t necessarily the one you employ with friends and co-workers. In a world where we’re all encouraged to think of ourselves as broadcasters, it’s only natural that we’d start to do a bit of branding on ourselves and our personalities.

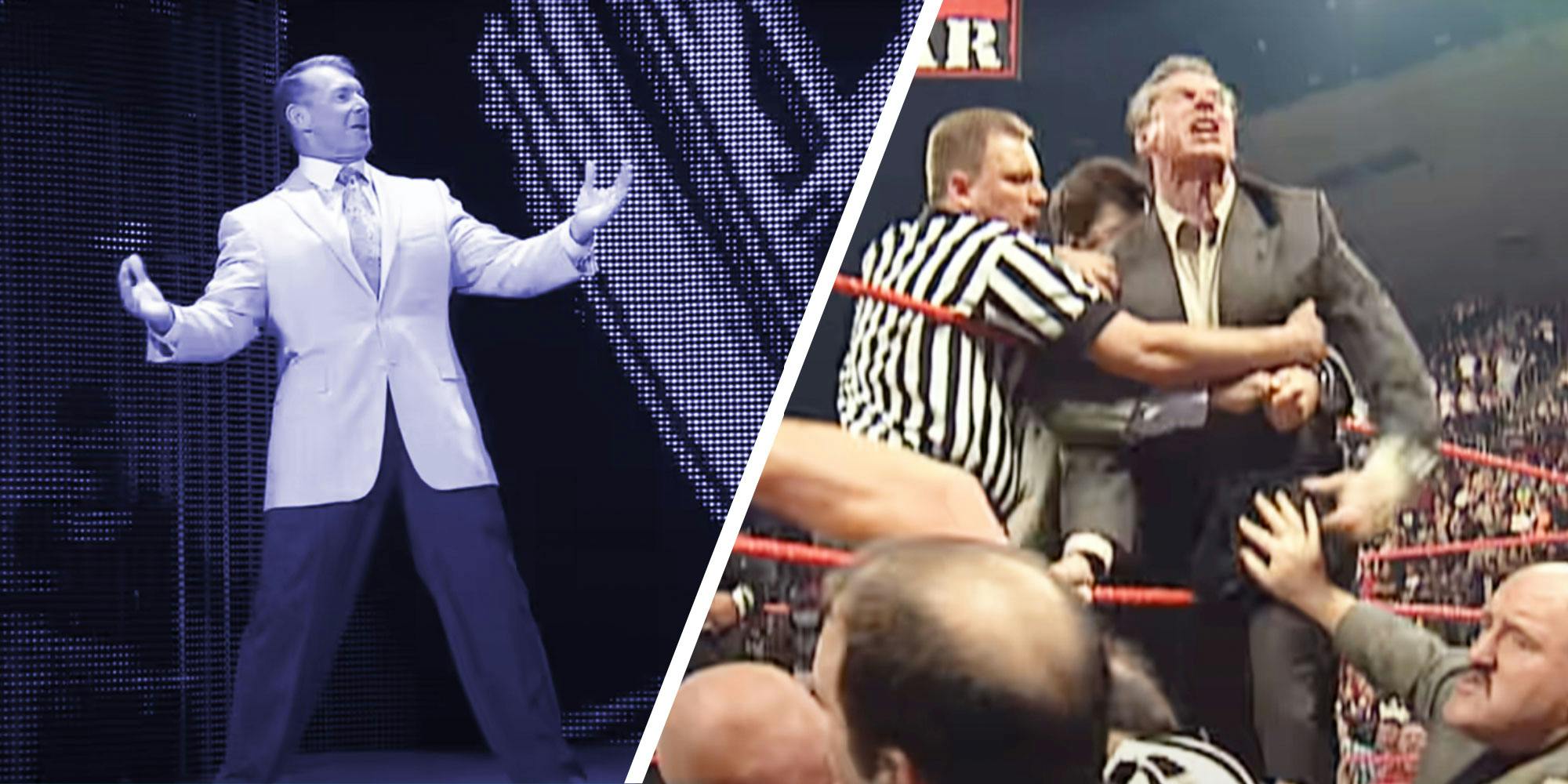

But pro wrestling does give us some insight into the inherent dangers of this practice, over time. And getting “lost” in the idea of publicly playing a character every single day. The story of Vince McMahon himself is something of a cautionary tale here. His wrestling persona, villainous billionaire “Mr. McMahon,” took on a life of its own in the 1990s and 2000s, during the WWE’s so-called “Attitude Era” and his on-camera feud with wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin.

The “Mr. McMahon” character was a crude womanizer and misogynist who serially abused and brutalized his staffers and his own family members, and whose business was the very definition of a “toxic workplace.” Over the ensuing decades, we’ve now learned that many of these depictions – which were played as cartoonishly over-the-top comedy – were, in fact, chillingly accurate and rooted in everyday life.

Did the real Vince McMahon get lost in his character? Was he always like this, and used the fact that he was portraying himself as a comical villain on television as a kind of cover? (His constant refrain in the Netflix doc is that he’s not really a bad guy, and everyone is just confused because of his TV character, which adds some credence to that second one.)

On some level, it doesn’t even matter. Generating heat to attract attention is one thing, but creators only get one persona and reputation. It’s a similar lesson to the one learned by Herschel Beahm IV, better known online by his comically oversized and cartoonishly aggressive persona, “Dr. Disrespect.” Once among the internet’s most popular gaming livestreamers, Beahm’s reputation took a massive hit earlier this year after he admitted to inappropriately contacting an underage fan. When asked recently about a possible deal to bring him over to Kick, co-founder Eddie Kraven said such a deal would “make zero sense” and would be a “waste of money.”

4. Everything Gets Stale Eventually

One of McMahon’s key rivals throughout his reign at WWE was Eric Bischoff, who served as an executive producer and VP for Ted Turner’s competing wrestling promotion, WCW. Bischoff and McMahon often borrowed performers and ideas from one another, and for a notable period in the late 1990s, WCW actually managed to lure away a lot of top WWE talent and surpass them in the TV ratings for over a year.

But by Bischoff’s own account, once he had established dominance in primetime on Monday nights, he allowed WCW to stagnate and stopped innovating and coming up with new ideas. Relying on a roster of popular wrestlers and an in-your-face approach that skewed toward older viewers had worked out great, and Bischoff naturally assumed it would continue to work in the future. But by adapting or borrowing a lot of Bischoff’s ideas, and introducing a large roster of fresh talent (including The Rock, Steve Austin, and others), McMahon was ultimately able to recapture and hold the audience’s interest. Within a few years, WWE had acquired WCW and Bischoff was working for McMahon, overseeing the company’s “Raw” brand.

The lesson here for online creators: you can’t ever rest on your laurels. Channels and platforms and personalities need to constantly reinvent themselves, and explore new approaches and fresh ideas, or risk this same kind of stagnation. For content creators who appeal specifically to younger viewers, there’s a real and immediate danger of audiences simply “aging out.” 13-year-olds develop very different tastes by the time they’re 16 or 17. If their favorite creators are not constantly seeking new audiences, or growing along with their communities, they’re very quickly going to pass out of fashion.

Even iconic and beloved shows and formats that have remained vital and popular for years or decades need a fresh coat of paint and a new perspective now and then. Go back and watch an Honest Trailer from 2014 vs. one made today and you’ll spot the differences immediately. “Hot Ones” is not going away any time soon. But they’ve started hosting fictional and even animated characters just recently. In short, there’s always room for innovation.