Like all creators, those who focus on science make content for free on their various social media channels. But unlike creators in some other fields, multiple science creators and experts told Passionfruit monetizing their science content through brand partnerships brings up some hard questions.

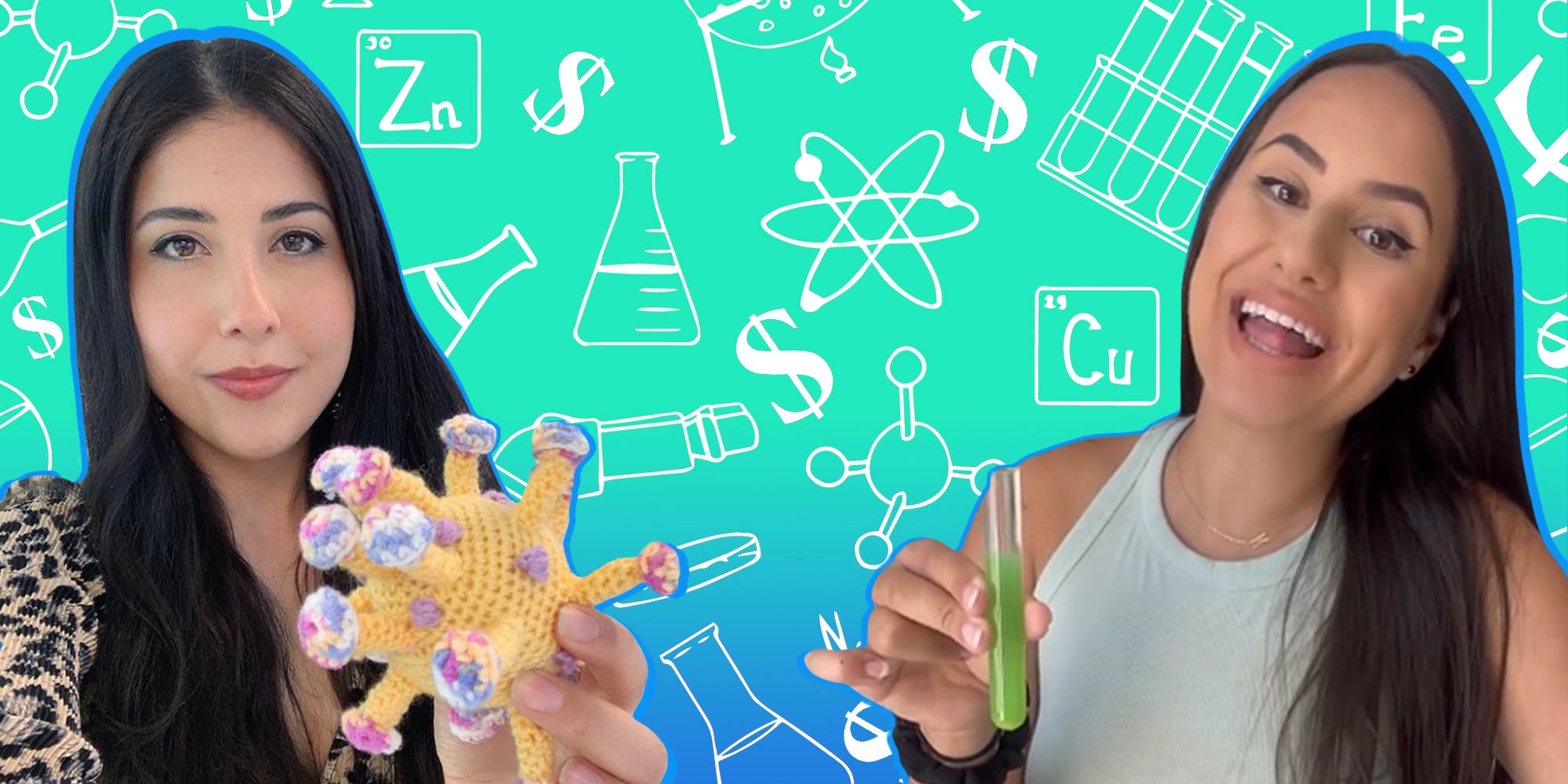

At first appearance, Dr. Sarah Habibi and Dr. Samantha Yammine seem pretty similar. The two are both science creators in Canada with around the same number of followers. Habibi, better known to her cumulative 161,000 followers as @science.bae across both Instagram and TikTok, mainly posts about at-home activities in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) and her life as a working mom. Yammine, better known to her cumulative 141,000 followers as @science.sam across both Instagram and TikTok, mainly posts about science from the perspective of a researcher and biologist and is well-known for her explaining the science behind COVID.

The major difference between these two is the way they approach brand deals. Habibi has partnered with brands like Olay, Secret, and Vicks, while Yammine is more selective about her partnerships.

For Habibi, the two concepts of business and science “go together” seamlessly because, she said, “My business is making content, and it’s content in STEM.”

Meanwhile, apart from the occasional partnerships with organizations, like the Ontario Science Centre or technology company 3M, Yammine told Passionfruit she doesn’t mind being selective about who she works with.

“From a financial perspective, it might sometimes hurt me,” Yammine said. “I could probably be making a lot more money, but I center my values in everything I do.”

The nature of being a science creator creates a divide on how to approach brand deals. The field is a new one—and nobody is quite sure how the money marking part of it fits in.

“The public needs experts they can trust when they have scientific questions, and they are particularly attuned to the corrupting power of money,” Jonathan Jarry, a science communicator at the McGill Office for Science & Society, told Passionfruit in a statement via email. “Science communicators need to be mindful of that and weigh their integrity against the need to put food on the table in these difficult times.”

Though there’s no framework for science-creator partnerships, Habibi and Yammine agree the most important thing is scientific accuracy. They said they both do their own research about the science the brand presents them with to ensure that it’s up to their scientific standards. They both have PhDs (Habibi in molecular biology, Yammine in neuroscience and cell biology), so they know how to do proper scientific research and understand clinical trials.

Habibi told Passionfruit she has three criteria she looks for in a brand partnership: Firstly, does the brand align with her values? Secondly, does it pay her regular rate? And thirdly, does it have scientific content involved? Once a brand hits at least two of those three points, she explains, she’ll move forward. If scientific content is involved, that’s when she’ll do her own research to determine that the science is accurate.

For instance, when Habibi was pregnant, she was offered a partnership with a cream that would remove stretch marks and tighten skin. But she said the science wasn’t there, so she declined.

“There’s very few ways to actually remove stretch marks, and a cream that is claiming to remove stretch marks, it’s just not true,” Habibi said. “Everything I do has to be evidence-based.”

On the other hand, Yammine has a few more partnership guidelines. She has a clause in her contracts for scientific accuracy and, like Habibi, does her own in-depth research about any science involved with the brand or product. Yammine also said she writes her own content for partnerships and won’t just read promotional scripts written by brands. In addition, she won’t participate in a campaign that doesn’t have equitable representation.

Yammine added she refuses to do any pharmaceutical partnerships due to not wanting to threaten her integrity and credibility around information about COVID vaccines. Anti-vaccine trolls already call her a “corporate shill” for educating her followers about vaccines, and she doesn’t want more of that.

“People value my opinion as a scientist, and I’m very careful with how I wield that,” Yammine said.

Habibi’s and Yammine’s processes may sound intense, but more non-science creators are now requiring this kind of information from brands, Sarah Hickam, head of talent at influencer relations and talent management company Shine Talent Group, told Passionfruit.

Hickam has worked with creator specialists like doctors, dermatologists, and nutritionists, but also has a large roster of lifestyle, fashion, and food creators. Many of the influencers she works with ask questions to brands before they sign, such as: What responsibility do you take with the waste from your products? What is in these ingredients?

“You would probably be surprised at how many creators say no to partnerships,” Hickam said.

Even brands are starting to ask questions about creators, Hickam said. If it’s an eco-friendly brand, they’ll ask questions like, “Does the creator promote single-use plastics?”

Brands, such as manufacturing company Procter & Gamble (P&G), even started to employ science communication teams to help creators understand the science behind their products, like Downy and Olay.

The Olay science communication team consists of cosmetic scientists and communications professionals who help break down the science behind their product formulations, according to Olay’s principal scientist, Dr. Rolanda Johnson Wilkerson. These scientists also work with product development teams and dermatologists to test and evaluate Olay’s products.

“The work that our team does ultimately supports the communication of value and efficacy regarding the products,” Wilkerson told Passionfruit in a statement via email.

Habibi worked with the Olay science communication team for her campaign about the brand’s reformulated micro-sculpting cream. She also did her own research about the science communication team’s claims about the efficacy of skincare ingredients like retinol and vitamin B3 to ensure Olay’s science was accurate.

Despite the rigor of science creators to ensure their science is accurate, science academia hasn’t always been friendly to their efforts. Habibi said she has been called a “sellout” by some academics. A researcher criticized Yammine in the prestigious science publication, Science, by claiming, “Time spent on Instagram is time away from research.”

The catch-22 of it all is there aren’t that many academic science roles. According to a paper for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, less than 15 percent of new Ph.D. holders in science, engineering, and health-related fields found tenure-track positions within three years after graduating in 2010.

Additionally, according to Jarry, jobs in science communication and science journalism are also not easy to find. This means being a science creator is one of the few accessible options for those looking to combine their skills in science and communications.

Furthermore, science creators are doing the work of combatting scientific misinformation (unknowingly spreading lies and bad information) and disinformation (knowingly spreading lies and bad information) by putting out credible science online. They’re up against “The Disinformation Dozen,” a group of 12 creators who are responsible for 65 percent of all anti-vaccine content. These disinformers make millions of dollars from their social media presence, mostly due to selling things like unproven cancer treatments and $497 documentaries about pet cancer to their followers.

“The people who are doing this to make money are the disinformers, making millions of dollars. I’m not making that,” Yammine said. “This is why the standards are so critical to me and why I’m so cautious about the types of brand deals [I take,] because there are people out there who use social media just to make money spewing pseudoscience and nonsense.”

This scientific rigor is reflected in science creators’ pricing. Habibi charges between $4,000 to $6,000 for a TikTok video. She knows this is on the higher end for her reach (the exact prices influencers charge vary for TikTok videos), but said her scientific rigor and Doctor title offer credibility and trust to consumers that brands value.

Yammine declined to disclose her rates for this article but said she does something similar to Habibi: part of her rate includes the time it will take for her to do an in-depth review of all the data and information given to her. She said she encourages science creators to reach out to her to learn more about pricing.

“There aren’t many of us, so we need to set the precedent for what a STEM creator is worth,” Habibi said.

According to Hickam, these premiums are justified for science creators.

“It’s definitely more niche…and brands should expect to pay a premium with somebody in that space,” she said. “It’s a smaller pool to pick from, as far as people in the world, and that’s reflected in the amount of influencers that there are.”

Yammine has one more unique, conditional part of her pricing: an “emotional labor tax.” This isn’t a literal tax or something that’s always included, but if a brand asks Yammine to share a personal part of her life, she factors into her rate the “extra labor and challenges” with doing that, including any backlash for posting about it. She encourages her creator friends to do the same—especially if it’s something that tokenizes or traumatizes them.

“You’re going to do pain porn of some difficult thing, you should be compensated,” she said.

As both Habibi and Yammine pointed out, the majority of their content is free to the public. It’s there for science communication purposes. It’s fighting disinformation. And above all, it’s getting people to actually like and engage with science.

With the science creator space being so small, especially in Canada, both Habibi and Yammine expressed how they feel they can lead the industry forward by setting high standards: for everyone to get paid well, for everyone to be included and for everything, especially sponsored work, to be scientifically accurate.

“This isn’t a very established career path, and this is not a very established niche,” Yammine said. “We can show people that this is how it should be done.”

Disclosure: The writer of this article did freelance public relations work for Habibi from August to October 2021.