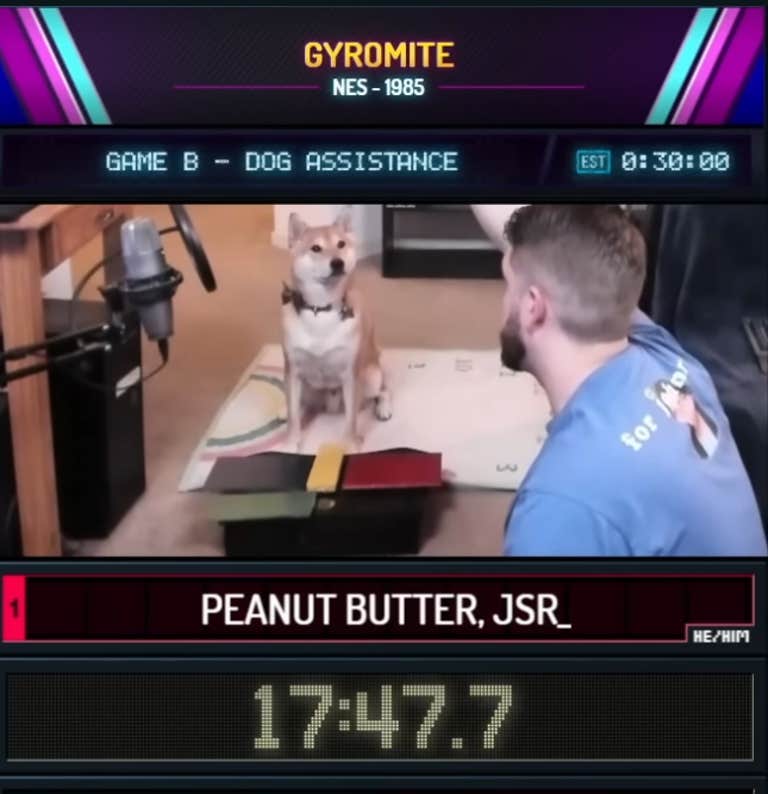

On January 2nd, a 13-year-old streamer who goes by Blue Scuti became the first recorded person in history to play a perfect game of Tetris. A few weeks later, a dog named Peanut Butter beat the 1980s Nintendo game Gyromite in less than 27 minutes. Neither of these milestones would have been possible without the community and culture that’s built up around the speedrun, meaning speedrunning video games.

Speedrunning is its own pursuit, separate from normal competitive gaming and esports. It’s less about competition and more about pure skill, so much that it may seem impossible when you see it done for the first time.

The carefully honed strategies and sequences that speedrunners use when they play are intense and difficult. But games are designed to be fun to beat, and a larger overview of speedrunning will show that it’s something anyone interested can attempt for enjoyment—and a chance at glory.

What is a gaming speedrun?

A speedrun is an attempt to beat a video game as quickly as possible. A speedrunner isn’t just trying to ignore any non-essential goal, but moving through the game’s world at the fastest speed, dispatching enemies most quickly, traveling the shortest distance, and so on.

Speedrunning is a collaborative effort, with players creating and sharing new strategies, tips, and tricks. There’s also a competitive element, since many speedrunners will try to set a record for the fastest completion, and many central communities for speedrunning like Speedrun.com or SpeedDemosArchive are built around the elite players attempting to set a record.

These elite players get recognition and achieve records the hard way. They have to play the same game over and over, dozens or hundreds of times, to eliminate all hesitation and master the game beyond what was intended, which includes using unintended elements of the game to beat it faster.

How does a speedrun work?

Since a speedrun is such an involved and competitive task, almost all games have a range of categories that a speedrunner can attempt. Instead of the entire game, a speedrunner can focus on speedrunning a single level or area. They may attempt a “100% run”, where they achieve every possible objective in a single playthrough, or the equally difficult “low percent” run, where they achieve as few objectives as possible while still winning.

Regardless of the exact way a speedrunner will try to beat the game, they will virtually always break from the intended way to play. Video games are complex pieces of software, so they universally contain unexpected processes or techniques. Sometimes, these are bugs, but sometimes, they’re unforeseen consequences of multiple other processes working together in the game’s code. A good example is “bunnyhopping” (also called “bhopping” since speedrunners, obviously, enjoy quicker ways to say things).

Bunnyhopping was first discovered in the 1996 game Quake. Games like Quake have physics simulation, meaning they don’t just track the player’s speed, but their acceleration and friction. A player who walks forward normally will reach a top speed because of their friction with the ground, but if they jump forward, touch the ground for the shortest amount of time possible, then jump forward again, the acceleration will have nothing canceling it out, and the player will travel much faster.

Speedrunning techniques get a lot more complicated and specific to certain games, but bunnyhopping is a good example of the category. Like most of these strategies, it takes precise timing and coordination to execute. Just like anything else done on a timer, speedrunning takes quick thinking and faster reflexes, as well as the patience needed to master both the conventional game and the advanced techniques.

How did speedrunning start?

The idea behind video game speedrunning is as old as video games themselves, but the earliest records we have of speedruns started online in the 1990s, in large part thanks to Doom and Quake.

Doom was one of the most ambitious 3D games ever made when it was released in 1993. The game broke sales records, established the first-person shooter genre, and introduced many features that are now synonymous with gaming writ large. One of these features was the ability to save a gameplay recording as a “demo” video, with a small enough file size that could be spread around the low-bandwidth 1990s internet.

Many of these videos were speedruns, but they tended to be shared in small, isolated communities. That would be different for Quake, which was an advancement of the technology in Doom. Quake emphasized the multiplayer elements of the game, leading to a wider and more connected community of players—and more desire to compete and show off.

1997 saw the release of Quake Done Quick, a video of three seasoned Quake players collaborating to beat the entire game on the hardest difficulty in less than 20 minutes. The video was a huge sensation all across the Quake community.

In a text file attached to the video (the internet was different 27 years ago), the runners were open about their ambitions: “There are several possible ambiguities to deal with when timing a demo […] We have settled on what we think are the most sensible ways of resolving them. We hope others will use the same methods.”

They made it happen. Speed Demos Archive, co-founded by a member of the Quake Done Quick team, became the most trusted way to track video game speedruns using the standards the team set. Along with Twin Galaxies, a website that tracked video game world records for Guinness, Speed Demos Archive helped speedrunning become more universally standardized as the new millennium began, and the evolving web allowed the community around it to grow into what it is today.

Also read about the first YouTuber—and other historical YouTube firsts

Who are the most popular speedrunners?

Speedrunning is impressive to watch, it’s easy to see why it’s become a spectator sport. Many speedrunners have fan communities, who follow their successes and failures as they hone techniques and attempt world records over livestream. Sometimes, the speedrunner will be popular enough their fans will follow them to less strenuous gameplay, or away from games entirely.

By far the most famous example is Dream. Also known as DreamWasTaken, Dream is an enormously popular YouTuber with over 30 million subscribers, and winner of the 2023 Streamy Award for Best Gamer.

Dream has become the figurehead of an entire community of streamers called the Dream Team, but much of the initial attention came from his skill as a Minecraft speedrunner. One of his earliest successes was “Minecraft Manhunt”, where Dream challenged his friends to kill his player character while completing a speedrun of the game.

Dream has stopped speedrunning after a massive controversy over a disqualified world record, but still enjoys the fruits of his success. Other popular speedrunners-turned-content-creators have remained in the game: Narcissa Wright, who founded the website SpeedRunsLive and set world records, was the subject of a 2023 documentary called Break The Game about her continued speedrunning attempts. Spikevegeta, who rose to prominence running Nintendo games, now organizes and commentates the biannual GDQ marathon.

How can I start speedrunning?

For the same reason speedruns can be electrifying to watch, they can be daunting to consider doing yourself. If you want to try your hand at speedrunning, there are only three pieces of advice you need when starting: Be patient, have fun, and don’t go alone. Speedrunning communities always welcome new members and will offer all the practical and emotional support they can.

Pick a game you enjoy, one that you will want to keep playing past the point of boredom and frustration as you build up the knowledge and muscle memory you need to go faster and faster.

Alternatively, if that sounds like too much work, just enjoy watching other people speedrun instead! A good place to start is the Games Done Quick YouTube channel or IGN’s Devs React To Speedruns series. Both feature a wide range of popular games from the 80s to the present day, and each video features extensive commentary and explanation that details the strategies and cooperation that make the incredible speed possible. Not everyone watching a 100-meter dash needs to go for a sprint to appreciate it, and you can enjoy speedruns in the same way.