In a new weekly column, writer Lon Harris examines how WGA’s organizing can work for the creative industry.

Analysis

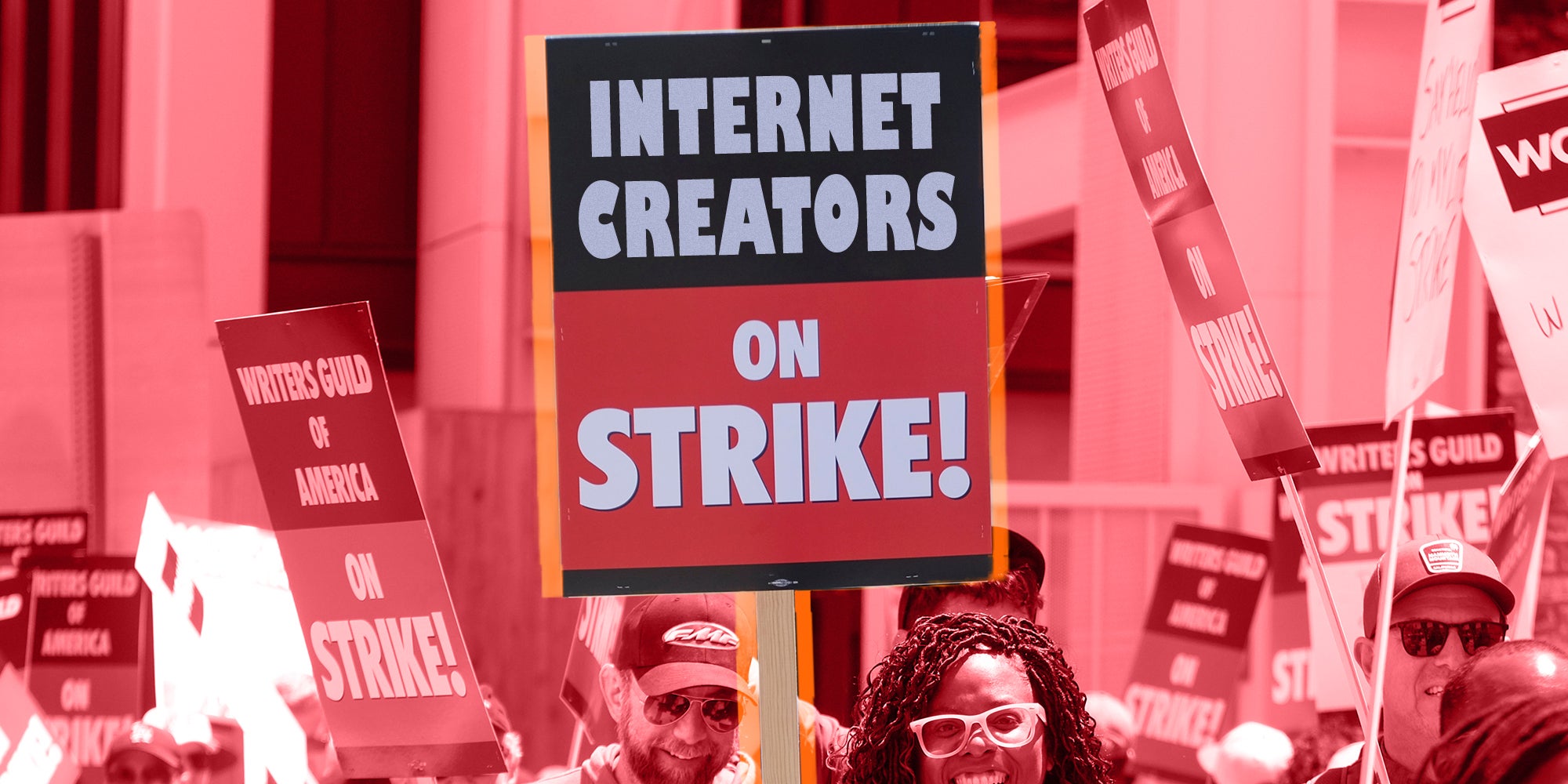

Hollywood productions are slowly grinding to a halt as the Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike enters its second week. Yes, the details of this strike may seem specific to TV scribes, but the battles being fought are the fallout of a larger transition within the media and communications industries.

That means there are plenty of lessons to be learned from the WGA strike for creators of all stripes, from highly-paid screenwriting legends to folks who just started their first TikTok account. Over the course of this new series, we’ll be looking at some points of comparison between the issues facing striking writers and the issues facing independent digital creators every day.

Networks, studios, and platforms are self-serving and unpredictable

Hollywood hasn’t been kind to writers since the talkies were a thing, so the plight of the screenwriter is not a new one.

But in recent years, a seismic shift has moved the industry away from its ostensible purpose of storytelling. Massive tech and telecom companies treat Hollywood film and TV production as a factory, with each new show or series another brick to slot into a homogenous house of on-brand genre content.

CEOs like David Zaslav of the newly-merged Warner Bros. Discovery earn tens of millions of dollars annually (or more) to look at all of their various holdings holistically and make decisions based on what will boost the stock and produce the highest short-term gains for board members and shareholders. Even in the case that CEOs are thinking about longer-term strategies to improve business, lucrative bonuses often ensure that they do their best to chase immediate gains.

While a studio boss during Hollywood’s Golden Era might have been concerned about courting top screenwriting talent and bringing them in to work on productions, Zaslav appears largely unconcerned with how his company’s movies even get from the concept stage to post-production. For example, he recently made an out-of-touch suggestion that striking writers will return to their jobs purely out of “a love for working.”

A growing divide

Digital creators don’t answer to studio chiefs when they’re making their own content. Still, by the time they build up any kind of sizable following, they will come to the attention of the mainstream entertainment industry.

But rather than utilizing creators as a vital lifeline to what online audiences are seeking out and choosing to watch for themselves, all too often, industry insiders seek to exploit creators and their audience, just as they would with professional TV writers.

Many extraordinarily popular digital-first creators have struggled to gain footing in film and TV, often through no fault of their own, but because the executives working on the business side don’t know how to properly use them and their particular talents.

What should have been TikTok star Addison Rae’s big introduction to late-night TV audiences—an appearance on Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show—turned into a scandal when the tone-deaf sketch failed to credit the Black dancers who invented most of the moves Rae performed. The 20-year-old influencer took a lot of the heat during the subsequent fallout, but after all, she had never produced a TV show.

On an even larger scale, despite promises made about the “digital economy” and its multitude of opportunities for everyone, a lot of social media platforms continue to exploit their userbases, taking huge chunks of their earnings with little transparency about how much money is actually being brought in and how many people are actually watching the content.

A lot of people are getting rich off of the boom in streaming and social media. Creator-focused apps generated around $1.3 billion in investment dollars in 2021 alone. But none of that money went to the people who make the content—instead, it goes to the entrepreneurs who start the companies and their investors.

The future isn’t looking bright. While a new study from Goldman Sachs predicts the creator economy will be worth half a trillion by 2027, Citi Bank also reports that platforms eat up 85% of creator revenue. Furthermore, with that roided up version of the Pareto principle, Citi Bank predicts only a handful of the 120 million creators currently making up the industry’s workforce will be able to get by without a day job.

The wrong interests

Executives’ business interests don’t always align with a creative project’s best interests. For example, economics 101 teaches us that the owners of the Batman franchise should make their insanely valuable intellectual property their top priority. Instinctively, we imagine they should focus exclusively on what will delight Batman fans and convince them to spend their hard-earned dollars on films and merch. But for DC Comics’ owners at Warner Bros. Discovery, the Batman franchise is simply another heading in their portfolio.

If it makes more immediate financial sense to throw a brand-new never-seen Batgirl film in the trash rather than releasing it to theaters or HBO Max, that’s what they’ll do—even if it puts a sour taste in the mouth of comic book readers worldwide (and convinces the people who wrote the Batgirl film to go on strike).

For independent creators, it’s crucial to keep this lesson in mind. Even if a platform, network, or producer is investing their money and time in a project, long-term, they can’t always be counted on to have that project’s best interests at heart. Executives have shifting mandates, and CEOs get fired all the time. Ultimately, it’s the creators who are going to have to speak up for and protect their own work.

There are many more takeaways from the situation facing WGA writers and digital creators, including the need for a lively and diverse community of collaborators, the importance of focusing on long-term career stability, and the significance of the human factor to all kinds of creative work. We’ll be back with more insights in our next edition.

Next week: Stay tuned for another entry on what creators can learn from writers’ unionization efforts and the history of the WGA.