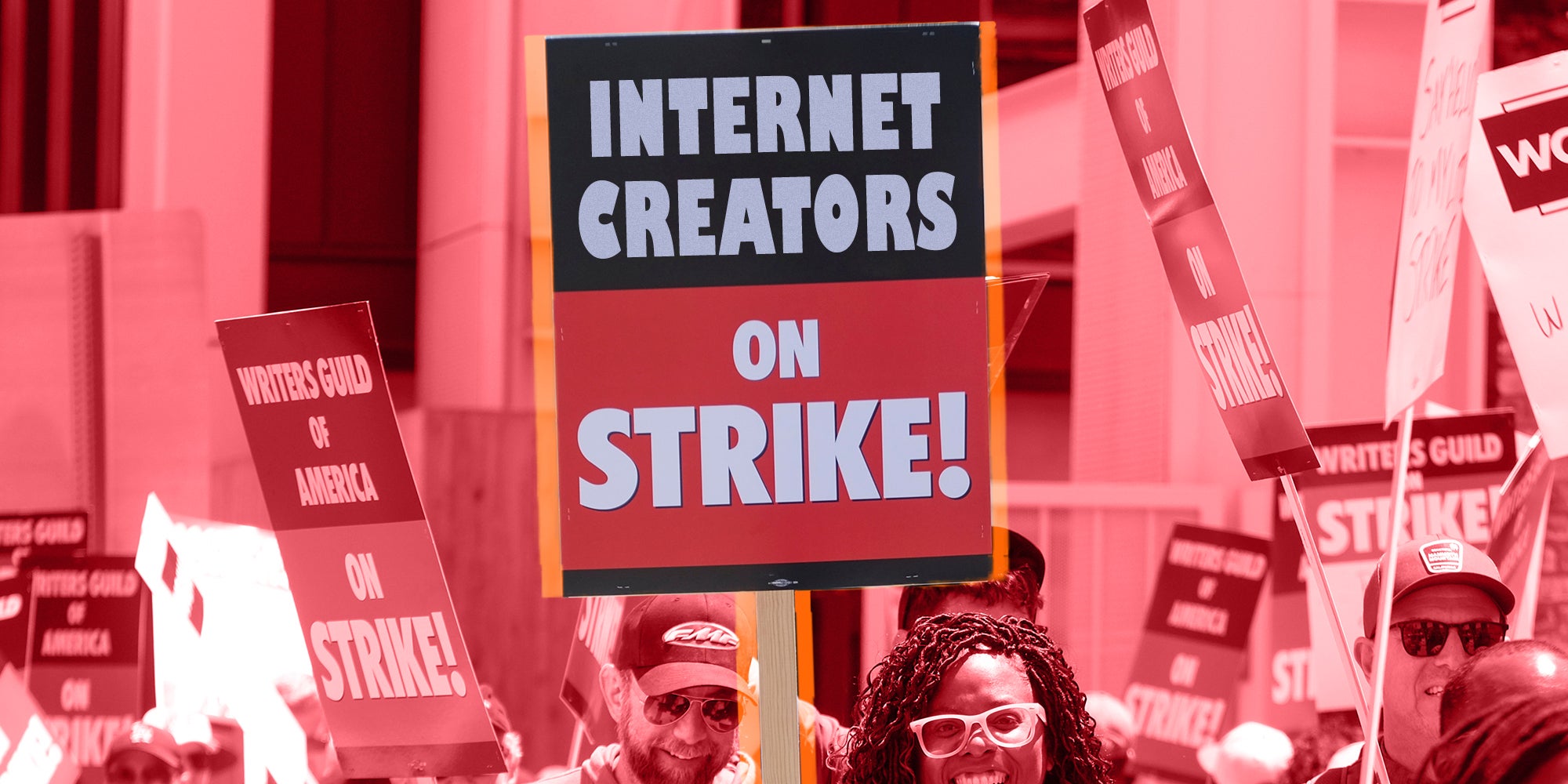

In a new weekly column, writer Lon Harris examines how WGA’s organizing can work for the creative industry.

Analysis

As Hollywood film and TV writers continue their effort to secure better deals from studios and streaming platforms, we’re continuing our ongoing series making thematic connections between the struggles facing these workers and the wider creator community. While it’s not always a direct comparison, many of the same issues facing film and TV writers have parallels for creatives working in social media, videos, and other digital mediums.

For example, the looming threat of job loss to artificial intelligence (AI) potentially impacts creators on every level, across the entertainment and technology industries and beyond. For the Writers Guild, nestled at the end of the last page of their proposals (which largely ask for fairer compensation and increased residuals) is a section about AI. It’s one of the first widespread attempts from a union to pressure industry leaders to regulate the use of AI to replace workers.

The concerns are not just about screenwriters being replaced by dialogue-generating robots. The WGA seeks to limit studios’ ability to employ AI at any point in the process—preventing the use of programs like ChatGPT to generate premises or concepts for films.

Currently, when it comes to screenwriting deals, the writer who originated a pitch or a premise gets special consideration. In a future where AI tools purchased by studios are the ones writing the pitches, writers could conceivably be left out of the most lucrative deals entirely, earning their money for rewriting the computers’ ideas, rather than building out stories and narrative worlds of their own.

The ‘blandification’ of media

The arrival of AI chatbots that could (at least theoretically) fill in for TV writers is just the latest in a long line of industry attempts to sideline actual humans in favor of technology-forward processes that can get creative work done without paychecks, bathroom breaks, or original thinking.

It recalls, in some ways, the “content farm” era of the 2000s and early 2010s, when heavy search traffic from Google, paired with the company’s AdSense platform, could translate into huge earnings for website owners and publishers. So-called content farms or content mills paid international freelancers phenomenally low rates to fill endless web pages with SEO-friendly, keyword-dense content designed to appeal to search engines.

Because the most important factor in revenue was search ranking and not the overall quality of work, many publishers fixated on generating more written content for less money, using technological shortcuts (like scraping other websites), or exploiting freelancers.

Rob Turner, writer and producer of the webcomic “Reynard City Chronicles,” recalls this era well, and drew a direct comparison to the current AI craze.

“As a digital creator, AI worries me because I have seen … other methods that have bypassed hiring writers to create content,” Turner told Passionfruit. “I fear a ‘blandification’ that will come off the back of [apps] making Frankenstein scripts from AI. We need distinct voices, stories that connect with people on both a universal and personal level. We need the human element, and it needs to be [paid] for the effort that goes into it.”

Recent efforts to integrate artificial intelligence into the TV assembly line while writers’ rooms are slashed down to a skeleton crew of part-time staffers are merely the latest development in an ongoing strategy, all aimed at the goal of generating more content (on which to place more ads) for less investment.

Not quite ready for prime time

Internet writers have already spent the first half of 2023 watching AI bots take over jobs that were once filled by humans. Buzzfeed was one of the first sites to boast of plans to increasingly replace human writers, utilizing AI overseen by freelancers for most of the site’s so-called “static content”—meaning links intended to stand the test of time, like quizzes, rather than breaking news stories.

A future where AI programs are capable of producing entire videos or ad campaigns based on simple prompts seems to be looming just over the horizon. Beyond the low cost and relative ease of producing “viral” content with AI apps, computer programs are also more malleable. A human creator might not feel that a certain concept works for their channel or audience, or may have their own ideas about how to present themselves and a product—an AI app will respond to any prompt without any pushback whatsoever.

Still, it’s a huge leap from writing a BuzzFeed quiz to writing an episode of Succession or curating a die-hard fanbase. While generative AI apps have thus far proven adept at certain kinds of rigidly formatted prose—straightforward queries, say, or standardized tests—most of their attempts at screenwriting and social interactions have gone viral for the wrong reasons.

In early May, right-wing commentator Ben Shapiro asked ChatGPT to write a TV comedy scene and posted the results. While he seemed to feel that the bot’s writing was cause for concern among TV writers, many commentators noted that the script lacked both a clear point-of-view and actual jokes.

AI also struggles with understanding what’s appropriate for its audience, or even what kinds of responses are going to be considered offensive. An AI-generated Seinfeld parody on Twitch had to be shut down in February after featuring transphobic remarks. Meanwhile, Snapchat’s “My AI” chatbot was immediately flagged for engaging in troubling conversations with the app’s young user base, including topics like sexuality and drug use.

Despite OpenAI’s attempts to give ChatGPT rigid guardrails preventing it from issuing forth intolerant responses, seeking end roads around these protections or ways to cheat the system has become something of a sport online.

Furthermore, a Guardian editorial from March points out an obvious downside to AI screenwriting: The bots exclusively train by reading pre-existing writing, so all of their ideas are largely obvious, expected, and formulaic. These are predictive language models, after all, not maps of William Goldman’s brain (he wrote The Princess Bride).

The proper use case

Unlike other kinds of assembly line work, where robots can take on some tasks while leaving more open-ended or creative work to humans, screenwriting isn’t done in a factory-type setting. It may simply not be the most appropriate use for these AI tools.

This isn’t to say these tools can’t have any applications for writers, online creators, and others. Many have found ChatGPT useful in a planning or brainstorming context, or for doing relatively mundane and repetitive work (like writing metadata tags, writing captions, filing taxes, responding to emails, etc).

But when it comes to making art, thinking imaginatively, or making new and compelling connections, it doesn’t seem like apps are ready to take over entirely just yet.

Content pays, but to make great films and TV shows—at least until the robots learn how to write better jokes—you still need human beings Similarly, while things like AI-generated bots might be helping content creators make some extra cash and talk to fans, nothing is going to compete for connecting with the real human behind the screen.

Projects come and go, but people come first

Though the film and TV industry’s initial plan was to stock up on fresh content prior to the strike, while shooting and producing projects that already had completed scripts, that’s proving increasingly difficult as the strike presses on.

WGA leadership has increasingly focused on ensuring that no writing is happening on any level, using picket lines not just to stir up support for the cause but actively interrupt sets and productions. The Hollywood Reporter estimates the shutdowns are likely costing studios between $200,000 and $300,000 per day.

The list of popular shows that have had their latest seasons interrupted grows each week, and now includes Loot, Good Trouble, The Chi, and Billions. Some high-profile shows, such as House of the Dragon and Andor, are moving forward during the strike—but without key creatives on set to help guide the actors and directors, it’s possible this could have a noticeable impact on the episodes’ quality.

Yet even fans have proved largely willing to put these disappointments aside, recognizing that the lives of the real people who create these shows hang in the balance. We all want to see Season 4 of Evil on Paramount+ (It’s really good and underrated!), but dark fantasy procedural dramas will always be around—people have to come first.

The pressures faced by creators make it easy to sometimes overlook personal concerns, or even health and safety, in favor of content. Videos, viral posts, and artistic projects aren’t worth those kinds of sacrifices—even if creators need to take a pause and rethink their approach. The potential audience clearly isn’t going anywhere.

Just as screenwriters are counting on their audience to ultimately miss their work and pressure studios to bring them back into writers’ rooms and onto sets, online creators can rest assured that they haven’t been innovated out of existence just yet.

Halfway through 2023, AI tools are impressive, but they remain simply tools, only effective in the hands of skilled human practitioners. Collectively, creators do still have power, and if they ceased posting, the world—along with the owners of TikTok, Meta, Twitter, and every other app relying on user-generated content—would certainly have to take notice.

We’ll be back next week with more insights for creators based on the WGA strike and its impact on the entertainment industry. Specifically, we’re checking out all the writers’ efforts to keep people informed and engaged with their cause, and what creators can learn from their success.